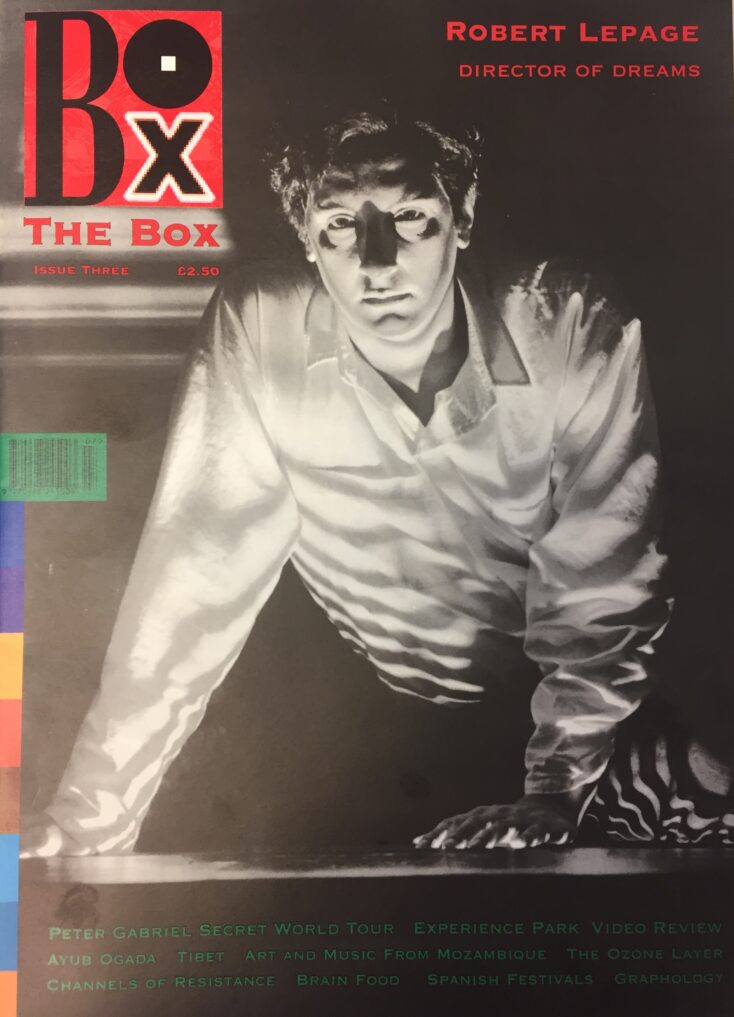

In issue three of Box Magazine, Martha Ladly interviewed Robert Lepage, Peter Gabriel’s collaborator on the set design for the Secret Word Live tour. Long out of print, the interview is reproduced on the website in full for the first time.

Robert Lepage is a French Canadian writer, actor, director and multi-disciplinary creator. From his background in 80s experimental punk drama to his position in the 90s mainstream, his work has always been highly visual and thematically wide-ranging. He works with traditional theatrical conventions and, using language and image as equal purveyors of his vision, radically transforms them. Recently Robert worked closely with designer Rolf Engel of Atelier Markgraph and with Peter Gabriel on the set design and staging of the Secret World Tour. I met Robert at the production rehearsals for the show. An animated but soft-spoken man, energy teems below the surface of his carefully chosen words and his intense, spectacularly eyebrow-less gaze.

Robert Lepage grew up in Quebec City, the child of French-Canadian parents; his father a taxi driver, his mother a housewife, with an elder adopted English Canadian brother and sister, and so both languages were spoken at home. In Robert, French and English collide and the resulting impact gives a creative tension to his personality and to his work. He compares himself to Frontenac, the famous French provincial governor of Quebec, who said to the British – “Je leur repondrai par la bouche de mes canons” – I will remember them with the mouth of my canon. Sometimes rejected by the Quebec critics precisely because of his success in the English speaking theatre, his regarded as somewhat of “un oiseau bizarre, un étranger” by his peers. He is in fact a true post-provincialist, a post-nationalist. The work of Robert Lepage is not fuelled by the motor of provincial politics or linguistic jingoism. His is work to export.

Robert is someone who needs to travel, to be constantly on the move, to change styles and disciplines. He is hard to pin down, difficult to define. He was in therapy for two years, but found it impossible to talk about his problems, which he couldn’t put a name to. It wasn’t until he became involved with the theatre, and acting in particular, that he found a way to create a mask for his fears. He says “the theatre has one special characteristic. It is always possible to start again. In life this is a myth; we ourselves can never go back, we can never have a second chance. In the theatre the slate is wiped clean every time.” The attraction is obvious, but pain and conflict, difficult experience and struggle have all given a voice to his extraordinary work.

Robert first came to international attention in 1987 when his play “Vinci” was performed at the ICA in London. With Vinci, Robert was inspired by the Da Vinci cartoon of the Virgin that was shot-blasted in the National Gallery. The piece explores the relationship between acts of creativity and acts of violence. Da Vinci himself was a man of immense contradictions: he was obsessed with human suffering, and yet a great inventor of war machines. He waged a constant personal battle between the intellect and the spirit, the head and the heart. The play deals with the suicide of a young artist film-maker who slits his wrists when the project which inspired him fails from lack of funding.

In 1989 “Polygraph” toured throughout Europe. The play is based on the true story of the murder of his close friend, a young actress in Quebec City. Robert and a number of friends in the theatre became suspects in the murder case and had to undergo questioning and polygraph tests. When the murderer was arrested and finally convicted he was able to use the material in a play. The work became an act of mourning but it also became a way from Robert to untangle the events and to address the moral issues involved. In Polygraph he explores the telling of a true story, the ethics of film-making and the effects of death upon the living. “I was looking for a way to tell a story that would inform the human soul.”

“The Dragons’ Trilogy” was performed in the UK in December 1991, but it has been performed as a work in progress throughout the world since 1985. It played for six hours and covered 70 years of cultural confusion in Canadian history, providing a more exciting six hours than the subject should have deserved (and I’m Canadian). In the play, two Chinese sisters disappear into the bowels of ancient China, buried underneath a car park in contemporary Canada.

In “Tectonic Plates”, another on-going international co-production, Robert tackles the subjects of identity, geography and sexual politics. It is an epic play about continental drift, with some very funny scenes set in restaurants. A sensitive actor and relayer of emotion – he played Pontius Pilate in the film “Jesus of Montreal” – Robert plays a good-looking transsexual. In the part he explores the meaning of gender – which he says is “not sex, as we know it, but the sex of the soul”.

Last year Robert Lepage became the first North American to direct Shakespeare at the Royal National Theatre in London, with his production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”. Performed entirely in a pool of primordial mud, the production unearthed the profound sexual darkness and nightmarish eroticism of the play. Some of the critics were horrified. Richard Eyre, Artistic Director of the National Theatre was not. He says of Robert, “His work isn’t avant-garde or experimental but neither is it conservative. It’s its own thing – a theatrical syntax that expresses sound, light, language, movement, music and performance. It has wit and it has humanity. It is elusive but accessible. His theatre has the logic of dreams.”

Last year Robert toured internationally with his most recent one-man show, “Needles and Opium”. The performance was a tour de force dealing with addiction, phobia, mania and irresistible urges; a meditation on love, loss and art. In the play, he compares his own love affairs and emotions to those of Miles Davis and Jean Cocteau. He looks at what happened to Miles when he split with Juliet Greco and started down the road of his drug addiction, and at how Cocteau behaved when he lost his lover. The subject of drugs and religion is dealt with and the metaphor of a massive syringe is used: “Religion is the opium of society and also opium is the religion of society – what we expect from religion is explanations and what we want from drugs is explanation – we need both, we get neither.”

Robert believes that theatre has a moral and social way of communicating to the human spirit that film is still trying to find. Never-the-less he is inspired by film and the filmic method of story-telling. He glories with the stage and loves to be on it. He likes to play and believes that it is his role to direct actors to play. So he brings in playful elements – in “Needles” his character emerges from a swimming pool, trumpet in hand, making phone calls to his love on his Bell Canada calling card, in “Dream”, the players wallow in the mud splashing actors and audience alike.

PG and Robert Lepage. Rehearsals for the Secret World Live tour, 1993. Photo: Stephen Lovell-Davis.

The Secret World Tour production design presented Robert with the challenge of integrating the intimacy and very personal nature of the music on US into the impersonal environment of the large arena settings that the tour will be playing. “The emotions on US are very complex, going from the solitary notion of oneself, to the relationship of the couple and out into the wider context of the world, US, everyone.” Robert wished to explore all of these relationships, and to use the design of the stage to personify the male and female, the singular and plural nature of US. He also wanted to provide a space where these interpersonal relations could be clearly acted out. So the stage production shows US and becomes US at the same time. Robert plays with the themes of collision, clashing, meeting and overlapping and resulting separation – the sexual and personal aspects of meeting and then pulling away again.

“The square stage represents the male and the round domed stage the female, the walkway between them providing communication and the link between the sexes. The link also becomes a road or a river, a place of travel and transformation, from one stage literally to another.” In other senses, the round stage symbolises the organic, hope and the world. The square stage is the urban environment and it contains the projection screen. There is much about water and about fire in the music and these images are also projected on-screen. The lighting design has been used to effect fire and water. The result is one of the most moving and emotional platforms for a popular music concert ever conceived.

Robert Lepage has no end of future plans – for theatrical productions, film, opera, the development of an arts centre in Quebec City and a project for the fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, for which he would like to learn Japanese.

To find a key to Robert Lepage, I looked back at “Needles and Opium.” Although their personalities are almost opposite, Robert feels particular affinity with his two great heroes, Miles Davis and Jean Cocteau. Apart from his love jazz, he says, like Miles, his own personality is cool and unrevealing. And like Cocteau, Robert wishes to convince us that there is more to life than just what we see; that with the pen or the eyes of the artist, reality can be pierced and, even if only briefly, the metaphysical will flood in. Robert Lepage makes dreams come down to earth – and like Cocteau, gives us vertigo in the process.

PG and Robert Lepage. Rehearsals for the Secret World Live tour, 1993. Photo: Stephen Lovell-Davis.