Richard Blair spent a number of years in the late 1980s & early 1990s working at Real World Studios as a house engineer, primarily assisting Peter’s main engineer at the time Dave Bottrill.

Richard went on to form the group Sidestepper, whose album Supernatural Love was released on Real World Records in February 2015, but here he recounts how the time spent working with Peter has been instrumental in his development not only as an engineer and producer but as a songwriter and artist.

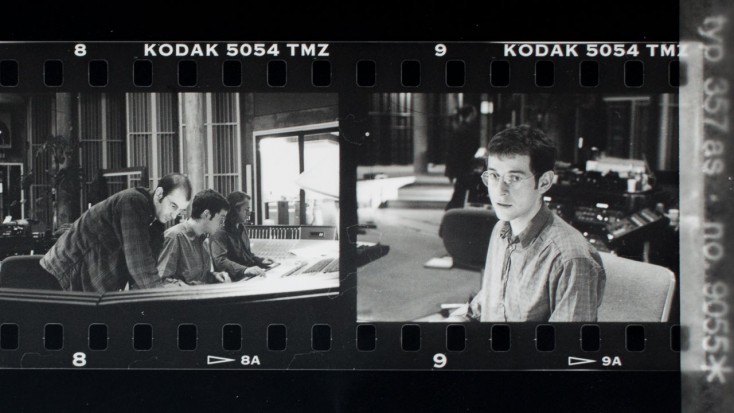

Dave Bottrill, Richard Blair and Peter Gabriel. The Big Room, Real World Studios

“I was ostensibly hired as the assistant to master engineer Dave Bottrill, and the job was to learn engineering and literally ‘assist’ him in whatever ways he needed. One of those was tidying up the studio, but I wasn’t very good at that. I was also way out of my depth technically, not really able to be much help with synchronising three tape machines or getting guitar sounds. Early on in the process Peter told me that he liked to have a DAT tape running at all times. Whenever he was in the room and there was music happening we had to be recording it, catching whatever ideas were popping up by plugging the stereo output of the desk into the DAT player. Next time we worked on the song Peter would remember that he’d played a keyboard riff, or sang a vocal idea, and would ask to hear the reference, sometimes weeks later. In order to be able to get back to those references I wrote a running commentary on the sessions in a big double entry ledger book, and a phrase like ‘lovely keyboard line, high melodic’ – 1 hour 43 DAT # 25 – would be enough to go straight to the lick Peter had remembered playing. From there he could play it again or hearing it would inspire him to take the idea somewhere else.

At the beginning Peter would glance over and make sure that the good idea had been noted, that I’d got it down and it had been safely logged. As time went by he began to trust me a little more, I began to read the music and the situation better and those glances were no longer necessary, he knew that if something good had happened I would have noticed. After a few years doing this it began to work like a mirror, and at times Peter would look up to see if I had noted anything down, to see if I had thought it was worth noting. That was a major revelation for me, and a huge vindication, that my instincts were good enough to hold my own with the best in the business.

The Big Room, Real World Studios

By the end of the US record we had hundreds of two-hour tapes, many log books, and amongst all that information were the real nuts and bolts of how Peter made the record. It was often just me, Dave and Peter in the room, and we grew to know each other very well. It was the most amazing privilege to see how he wrote and made the album, up close and in detail over three years. Everything I’ve done in the studio since has been formed by that education. Both Peter and Daniel Lanois instilled in me the vital importance of capturing magic, that we’re in the business of getting that on tape, and all the technical and preparatory work in the studio is only a means of creating the conditions where magic can fly. Our job as producers and engineers is to make the process transparent.

“Hey Peter, the kid can do beats, let’s get him working on your record” – Daniel Lanois

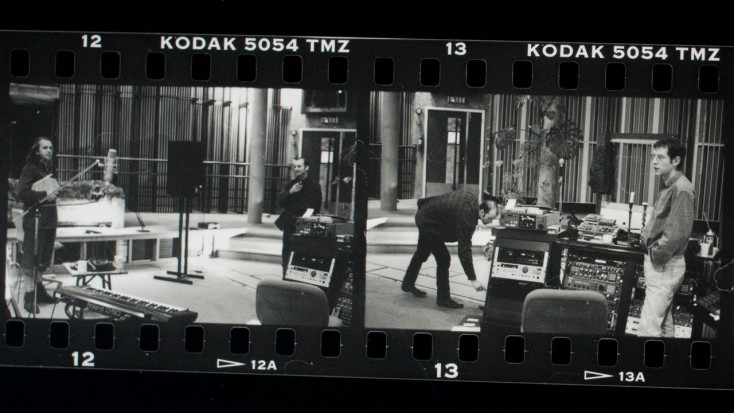

I’d seen how guys like Smith and Mighty and Massive Attack were sampling and making electronic beats, going after the holy grail of the perfect beat and bass line, something so sonically and rhythmically attractive that it would support a whole tune. Peter Gabriel was making his record US with Daniel Lanois producing, and Dan was travelling between Dublin and Bath doing the U2 record Achtung Baby at the same time. He was convinced that the emerging digital technology and the influence of dance culture on music meant we should use these sounds and techniques on Peter’s record. I’d been tinkering about with samplers and beats, and he noticed. I forget if there was one thing he heard that convinced him, but one day he said to Peter, in that very American can-do kind of way, ‘hey Peter, the kid can do beats, let’s get him working on your record’. I think Peter may have been a little reluctant, I was only the assistant engineer to Dave Bottrill, and maybe he felt this would be crossing the line between engineers and players/producers.

Daniel Lanois and Richard Blair at Real World Studios

Anyhow, they let me get on with it. I would stay late at night after Peter, Dan and Dave had gone, and put up the tapes of the song they wanted me to work on. Making beats involved a lot of craft back then, and I was getting into that delicate and subtle world of moving and tweaking the loops and sounds until they started to swing. The next day the Bosses would come back in and give it the thumbs up or no. Most of the things I did ended up being blended with existing rhythmic elements or used as a base for future Manu [Katche] drum tracks. However, there is one beat I remember doing for the song ‘Kiss that Frog’. Again I’d been up very late on it, totally fired up by this wicked swinging thing I’d done, an upbeat almost gospel jump up that hints at what was to come with sidestepper. The following night the guitar player David Rhodes was in for a session with Peter and Dan, and they put up the beat. They loved it, playing to the groove was making them happy and it really kicked off. I forget how many takes they did, but they just wanted to keep jamming on it again and again. I went home very happy that night.

As Sidestepper has progressed I’ve been very aware that I’ve tried to make records following Peter’s example, and perhaps the most obvious way has been the process of trial and error, following up moments of inspiration with a lot of hard work. Time is another tool in the box and it’s helped to let a tune or an idea just sit there, to come back to it months later and if it still sounds good there’s something of weight and value there. Perhaps above all what I learned from Peter is that you just have to keep working until it’s not just good, but the best one can do.”

Sidestepper in Bogota, Colombia 2015. Richard Blair, second left.